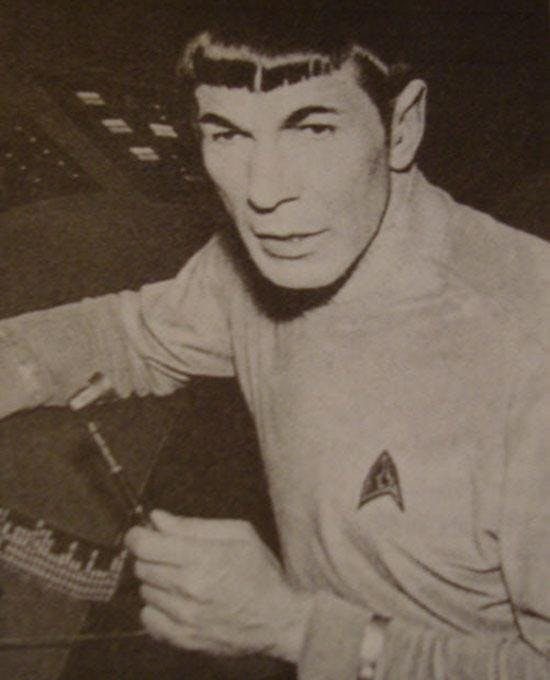

Gene Roddenberry poses with the three seductive characters in “Mudd's Women.” Image source: Unknown.

You ain't nothin' but a hound dog …

— Opening lyric for “Hound Dog”

Star Trek is remembered for breaking the cultural barriers of the 1960s, but it also reflects the sexual objectification and exploitation of women so common to the time.

Gene Roddenberry, the show's creator, was infamous around Hollywood for his sexual escapades. While married to his first wife Eileen, he had affairs with Majel Barrett and Nichelle Nichols, both of whom went on to regular roles in the series.

In Roddenberry's original March 11, 1964 sixteen-page outline titled, “Star Trek Is . . .” here's how he described the first pilot's captain's yeoman, then named Colt:

Except for problems in naval parlance, “Colt” would be called a yeowoman; blonde and with a shape even a uniform could not hide. She serves as Robert April's secretary, reporter, bookkeeper, and undoubtedly wishes she could serve him in more personal departments. She is not dumb; she is very female, disturbingly so. (Underline in the original.)

In the 1996 memoir he co-wrote with associate producer Bob Justman, Desilu executive Herb Solow claimed that Roddenberry hired Andrea Dromm to play Yeoman Smith in the second pilot because he wanted “to score with her.” Roddenberry wrote a sexist remark in an April 14, 1966 memo to associate producer Bob Justman that the captain's yeoman has “got some pretty good equipment already.” Apparently this was a reference to Grace Lee Whitney, who had just been hired to play Yeoman Janice Rand.

Solow & Justman wrote later in the book, “The Star Trek women seemed to be mirror images of Roddenberry's sexual desires.”

In her 1998 autobiography, Whitney wrote that she met Roddenberry when he cast her for a pilot called Police Story. After that failed to sell, he requested her for the role of Janice Rand. She drove down to Desilu to meet with him, where he described the yeoman as “the object of [the captain's] repressed desire.”

In her book, Whitney alleged that she was sexually assaulted by an “executive” while filming the episode “Miri.” We'll revisit this incident when we look back at that episode; for now, we'll note that some believe it was Roddenberry, although Grace declined to name her assailant. (Roddenberry died in 1991.)

Whitney was dismissed from the show shortly after the assault, suggesting that the set was a hostile work environment for female actors unwilling to play along. Grace wrote that Gene constantly made, “Passes, innuendoes, double-entendres, the whole nine yards.” If the MeToo movement had been around in 1966, Roddenberry might have lost his show before it premiered.

There were other incidents of sexual hijinks. Justman wrote that Roddenberry used Majel to play a sexually charged prank on a 33-year old associate producer, John D.F. Black. Roddenberry aimed Majel at Black, who was unaware of their ongoing affair, ordering him to interview her for a possible casting role. Majel eased into his lap and began to unbutton her blouse. Roddenberry and and other executives burst in on them to confess to the prank.

Gene Roddenberry and Desilu executive Herb Solow posed with three dancing girls for this gag photo during the filming of the pilot episode, “The Cage.” “Oscar” refers to Desilu president Oscar Katz. Image source: Memory Alpha, originally from the collection of Herb Solow.

The reason I bring up all this is that it reflects Roddenberry's attitude towards women, and may explain why “Mudd's Women” is so blatantly sexist.

The episode's premise traces back to the 1964 outline, a pitch idea called “The Women”:

Duplicating a page from the “Old West”; hanky-panky aboard with a cargo of women destined for a far-off colony.

This might have been crossed with another premise, “The Venus Planet”:

The social evolution process here centered on love — and the very human male members of our crew find what seems the ultimate in amorous wish-fulfillment in the perfectly developed arts of this place of incredibly beautiful women. Until they begin to wonder what happened to all the men there.

In “Mudd's Women,” Mudd gives the women a “Venus pill” to temporarily restore their illusion of youthful beauty.

As we discussed in the blog article about “Where No Man Has Gone Before,” “Mudd's Women” was one of three story ideas selected between Desilu and NBC as the premise for the second pilot.

The script was farmed out to Stephen Kandel, a 39-year old writer who was already a TV veteran, on his way to one of the more distinguished writing careers in Hollywood. Kandel took the premise from Roddenberry's “The Women” and added a character he envisioned as an “interstellar con man hustling whatever he can hustle; a lighthearted, cheerful, song-and-dance man version of a pimp.” Roddenberry envisioned more of a “swashbuckling” character. Kandel went off to write the script, which Roddenberry kept rewriting. Kandel's illness, coupled with the carnal overtones of the premise, led Desilu and NBC to proceed with “Where No Man Has Gone Before” as the second pilot.

But the script was written, so it was selected as the second episode to be produced. Roddenberry took story credit, while Kandel was credited with the teleplay.

The 1964 outline specified the duties of the Enterprise crew. Among them were:

Any required assistance to the several earth colonies in this quadrant, and the enforcement of appropriate statutes affecting such Federated commerce vessels and traders as you might contact in the course of your mission.

The “Mudd's Women” premise clearly falls into the latter category. We tend not to think of the Enterprise as a patrol car, but that's the role it plays in this episode. Recall that Gene Roddenberry was a Los Angeles police officer while he built his early writing career.

The teaser opens with a captain's log, “USS Enterprise in pursuit of an unidentified vessel.” It almost sounds like a line from Adam-12.

Kirk asks Spock if it's an “Earth ship.” At this early point in the series, we still don't have the Federation or Starfleet. The craft is not transmitting a “registration beam,” the space version of a license plate. The ship doesn't respond to Enterprise hails. In my law enforcement years, we called this failure to yield. Just as sometimes happens in police pursuits, the pilot flees in blind panic, ignoring the imminent danger of crashing into something (in this case, asteroids).

After the cargo ship loses power, Kirk orders that Enterprise shields be extended to protect the disabled craft from space rocks. Enterprise burns out all but one of its “lithium crystals.”

Harry Mudd and his three women are beamed aboard. Scott and McCoy admire the women the way a lion admires a gazelle. The women pose and preen as if delighted to be objectified. As they're escorted through the corridors, the mouths of male crew members hang agape. Fred Steiner's musical score sounds like what we might hear during a strip tease at a seedy gentleman's club. Camera angles focus on first their derrières and then their torsos. It's almost as if we're watching a cattle auction.

Mudd comments to Spock, “Men will always be men, no matter where they are.” Apparently the Enterprise has no gay or bisexual crew members, but then this is 1960s network television …

With only one damaged lithium crystal left, the Enterprise heads for Rigel XII, a lithium mining planet. The last crystal fails; the ship limps along on battery power. While en route, Kirk holds a hearing the way an arraignment might be held for our arrested traffic stop evader. Harry says he's taking the women to Ophiucus III for “wiving settlers,” the future version of mail-order brides. He claims that the women were recruited, which the ship's lie detector doesn't dispute.* According to Mudd, the women are “to be the companions for lonely men, to supply that warmly human touch that is so desperately needed.” The women confirm his story; they seek escape and companionship too.

The lie detector confounds Harry Mudd. Where have we heard that voice before? See the footnotes.

Harry hatches a scheme (in front of two security officers) to free himself. Somehow one of the women manages to purloin a communicator, which Mudd uses to contact the Rigel XII miners. (Wouldn't the transmission have to route through Uhura?) When the ship arrives, barely capable of sustaining orbit, Kirk offers to “pay an equitable price.” (Apparently money is still in use, or some equivalent.) One of the miners, Ben Childress, says he prefers a swap — the crystals for the women, and the release of Harry Mudd. Kirk replies, “No deal.” Childress replies that the crystals are so well hidden, Kirk will never find them.

Considering Mudd's infractions are relatively insignificant, it seems like a no-brainer, especially with the ship's decaying orbit. (We'll overlook the physics of orbital mechanics for this episode …) Beam up Harry after the crystals are obtained. Oh well.

The ship reduces life support to conserve energy, but they still have the power to beam down the miners, Mudd, and the women to Rigel XII. Seems to me Kirk could have kept them all aboard until the ship starts to spiral in, so they can die with everyone else. Oh well. The Vulcan Mind Meld™ has not yet been invented, but if this were a second season episode Spock could have torn it from Childress's mind. There are always possibilities.

Eve has enough of it. “Why don't you run a raffle and the loser gets me?!” She runs out of the shelter into the magnetic storm. Childress eventually finds Eve and takes her to his quarters.

The Venus drug begins to wear off. Childress calls her “homely” and claims he has enough money to “buy queens.” Kirk and Mudd burst in. Childress is angry to learn the three women are imperfect. Eve takes another pill to restore her beauty — only it's a placebo. Kirk replaced Harry's pills with a colored gelatin. The lesson, Kirk tells us, is to believe in yourself. Eve chooses to remain with Childress, while Kirk takes Mudd and the lithium crystals back to the Enterprise.

As the episode closes, a joking McCoy gestures that Spock's heart is behind the left rib cage — where his liver should be, as we'll learn in the future.

I understand this episode is a product of its time. It's meant to be playful, to appeal to an immature male demographic. But for a show that aired Thursday nights at 8:30 PM opposite family programming such as My Three Sons and Bewitched, it certainly was an odd choice. Mudd is peddling the 23rd Century version of mail-order brides. He's little more than an “intergalactic trader-pimp” as Herb Solow described him.

According to some accounts, NBC was nervous about using this script for the second pilot, but that was to produce a film they could show advertisers. Now that the show was sold and on the air, morals seem to have shifted. Advertisements ran in local newspapers across the United States during the week before the episode aired on October 13, 1966, with photos showing the “male order brides.” NBC played up the chauvinistic overtones of the episode.

Advertisements promoting the “male order brides” were printed in local newspapers across the United States in the week before it aired. Image source: Binghamton, New York Press, October 8, 1966 via Newspapers.com.

Mudd's women can be considered a metaphor for young female actors who come to Hollywood, seeking escape from a hopeless life, dreaming of a glamorous future. These women are vulnerable, and unscrupulous producers know that. The “casting couch” was around long before Harvey Weinstein. Harry Mudd can be viewed as one such predator, although he doesn't partake himself in the abuse. In any case, the better lesson to have been taught by this episode would be for the women to find their independence and self-esteem, but this was the 1960s, when such a message was rare on network television.

For all the praise we give Star Trek's progressivism, Roddenberry — like all of us — had his hypocrisies. This was the man who wrote a strong female character, Number One, for the first pilot, “The Cage.” Although Gene claimed over the years that the character was dropped because NBC didn't want a strong woman on the bridge, Solow & Justman wrote it was because everyone knew Gene had cast his mistress; it wasn't a question of Majel's talent, it was the conflict of interest.

In both pilots, the female crew members wore trousers like the males. But when Star Trek went to series, the women now wore mini-skirts and go-go boots. They served largely in passive subservient roles.

Once Star Trek went to series, it suffered a shift in tone for most women portrayed in the episodes. “Mudd's Women” was the emphatic statement that gender equality went only so far in the Star Trek universe. Only one female crew member, Uhura, has lines in this episode; the only other female crew member we see is a brief shot of an extra in a corridor as Mudd and his women are escorted to Kirk's quarters. We're otherwise led to believe that the Enterprise is crewed by a complement of rutting men.

Yvonne Fern, Herb Solow's wife, published in 1994 a book titled, Gene Roddenberry: The Last Conversation. The book was a collection of conversations she had with Gene (and Majel) in the months before he passed in 1991. On pages 101-102, Gene discusses the affairs he had with women outside his marriages. Gene said Majel was aware but, importantly for our insights, he regarded these dalliances as strictly physical, not intimate. In his view, he had done these lonely women a kindness by sharing his body with them. We're reminded of Harry Mudd's claim that he's uniting lonely men with lonely women.

Roddenberry's morality standards are not ours to question. I'm only quoting this to provide an insight to the man who originated this episode's premise that, by today's standards, would be considered chauvinistic. Beautiful women gave him a carnal pleasure. Nothing is wrong with that; in the 1960s Roddenberry was not alone in exploiting the female form, for network ratings or for some more personal ambition.

But one cannot hold up Star Trek as a crucible for examining the human condition without noting that it carved out an exception for the female gender.**

Some lexicon notes:

- As in the last episode, Uhura still wears a gold uniform.

- Mudd describes Spock as “half Vulcainian.” “Vulcan” is not yet in use as an adjective.

- The ship is still powered by “lithium” crystals. “Dilithium” is not yet a thing.

* Majel Barrett debuts in the series as the voice of the ship computer — in this instance, the lie detector. She'll return on-screen in episode 10, “What Are Little Girls Made Of?”

** Susan Denberg, who played Magda in this episode, apparently posed for a Playboy magazine pictorial around this time. The photos appeared in the August 1966 issue. It may be no more than an interesting coincidence, but should be noted.

Sources:

David Alexander, Star Trek Creator: The Authorized Biography of Gene Roddenberry (New York: ROC Books, 1994)

Yvonne Fern, Gene Roddenberry: The Last Conversation (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1994)

Herbert F. Solow and Robert H. Justman, Inside Star Trek: The Real Story (New York: Pocket Books, 1996)

Grace Lee Whitney with Jim Denney, The Longest Trek: My Tour of the Galaxy (Sanger, CA: Quill Driver Books, 1998)